This article is an opinion piece by committee member Professor John Wood and a foretaste of an evening of talks and discussion – Reclaiming the Commons, A St John’s Society Green Conversation Event, 10th March 2025. Tickets available here.

The Value of Trees

Why do we underestimate it?

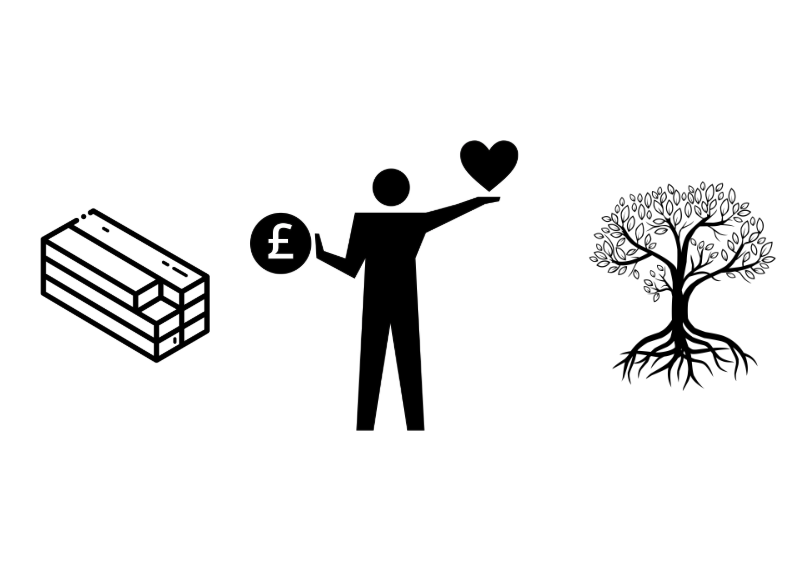

Each tree costs money

But when local councils remove them they may be reluctant to justify their decision.

Sometimes they blame engineers and/or insurance companies

e.g. Falling or failing trees hardly ever kill anyone in towns and cities (c.f. Way & Balogh, 2022)

e.g. Their roots can make buildings crack.

Economists try to account for them as though they are simple identical units.

This enables officials to claim that they have added value

(e.g. planted more trees than they removed).

But what do we really mean by value?

But what do we really mean by value?

Value is a tricky word when we confuse it with price.

Scientists like to explain the world in quantities, rather than qualities.

Politicians use numbers to manage communities (e.g. taxes & monetary incentives).

Large organisations think in numbers in order to balance the books.

Numbers are self-identical…

Humans like things to be simple & predictable.

And money is useful for trading dead things that can be quantified.

This saves time because we can all agree with the arithmetic.

Money is fungible

The monetary system hides the inconvenient complexities of trees.

Whereas money was designed to be fungible, living trees are limited by their ecological context.

Fungibility is a design feature of accountability that makes little sense within systems of responsibility)

…we try to make timber seem fungible

Numbers help us put a price on timber but don’t help us to value trees.

Trees may look identical on paper but each grows differently & supports different life forms.

They are alive until we break them down into standard units for pricing (e.g. as materials).

But when we regard things as the same we overlook important ambiguities and irregularities.

…living trees support biodiversity

However, as each tree is unique its role in the whole ecosystem is also unique.

E.g. a well established tree is likely to have more amenity value than a sapling.

The species of a tree helps to determine its value as host to a range of insects and animals.

Removing it may have a negative impact on the biodiversity of local ecosystems.

…the transition from real things to ‘values’

Managing remotely (e.g. from an office desk) means ordering by classification, then counting.

Insurance contractors estimate the likelihood of trees causing damage to people or property.

They may coerce Councils to reduce these perceived risks by recommending removal.

…the transition from ‘value’ to ‘price’

Some of the perceived negative liability value of a tree can be retrieved by converting it to timber.

In effect, each unique, living tree becomes quantified according to standards of unit pricing.

‘Priceless’ amenities (beyond value)

Saying that something is beyond value doesn’t clarify the issue in a practical way.

When we remove trees we hope to convert their amenity value to commodity value.

A tree’s amenity value reflects a human-centred value system – i.e. its capacity for:

- intercepting rainfall

- reducing air pollution

- carbon sequestration

- storm water attenuation

- urban climate adaptation

- making cities look more attractive

- local air cooling (shade / evaporation)

- reducing water pollution from rainwater runoff

Economic complexities

Trees sequester carbon from the atmosphere at different rates over their lifetime.

The amount depends on many factors, including:

- the species of the tree

- the age of the tree

- the size of the tree

- the health of the tree

- the location of the tree

- the tree’s exposure to light.

Huge discrepancies

Local councils, planners, landscapers and management companies face increasing budgetary pressure.

They are also increasingly responsible for report on and reducing their carbon emissions.

Unfortunately for them, the value of one tree can be over 100 times the value of another.

And most carbon offset methodologies do not sufficiently account for this.

They use averages to calculate a tree’s impact over long time periods.

‘The Law of Diminishing Returns’ applies to all fossil fuel enterprises.

By contrast, trees keep on giving – keeping us cool as climate change does its best to fry us….

In amenity terms they therefore behave in accordance with the Law of increasing returns (see Arthur, 1996).

Arthur, B. (1996) ‘Increasing returns and the new world of business’, Harvard Business Review, July/August 1996, p. 100

Corning, P., (2003), Nature’s Magic: Synergy in Evolution and the Fate of Humankind, Cambridge University Press, NY, USA, 2003

Gollier, C. (2013). Pricing the planet’s future: the economics of discounting in an uncertain world. Princeton University Press.

Graeber, D., (2011), Debt: The First 5000 Years, Melville

Jackson, Tim (2009). Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Sustainable Development Commission.

Maturana, H., & Varela, F., (1980): ‘Autopoiesis and Cognition; the realisation of the Living’, in Boston Studies in Philosophy of Science, Reidel: Boston.

Rapley, J., (2017). Twilight of the Money Gods: Economics as a Religion and How it all Went Wrong, Simon & Schuster

Romer, P., M., (1986) Increasing Returns and Long-run Growth, Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago

Jackson, Tim (2009). Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Sustainable Development Commission.

Pimm, S. L. (1997). The value of everything. Nature, 387, 231-232.

Romer, P., (1991), Increasing Returns and New Developments in the Theory of Growth, In Equilibrium Theory and Applications: Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium in Economic Theory and Econometrics, edited by William Barnett et al.

Simmel, G., (1900), The Philosophy of Money”, Routledge; New York & London, p. 259

Way, T.L. and Balogh, Z.J., 2022. The epidemiology of injuries related to falling trees and tree branches. ANZ journal of surgery, 92(3), pp.477-480.